Juneteenth marks a major event in African American history. African Americans were celebrating Juneteenth long before it became federally recognized just three years ago. These celebrations include foods that have historical roots tied to the slave trade, like soul food. In this article, we reflect on the significance of Juneteenth, the history behind soul food, and highlight two Black culinary pioneers who have left a legacy in the culinary world.

What Is Juneteenth?

Short for “June Nineteenth,” Juneteenth recognizes June 19, 1865. This was the day that the Union Army made it to Galveston, Texas, announcing to the people of Texas that all enslaved African Americans were free. Although the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in 1863, it wasn’t implemented in areas that were still under Confederate control. There were enslavers in Texas who knew about the Proclamation, but slaves in Texas weren’t freed until the Union Army intervened in 1865.

Juneteenth marks the United States’ second Independence Day. Although it has been celebrated in African American communities for generations, it didn’t become a federal holiday until 2021. This day serves as a time to celebrate the independence of African Americans while recognizing that although we have made great strides towards equality, the work is far from finished.

Juneteenth celebrates a pivotal component of African American history. A wide array of foods can be seen at a Juneteenth celebration. Red foods are common, signifying the cultures that would have come through Texas in the later years of the slave trade. Soul food is another common cuisine seen at these celebrations. Like the symbolism behind eating red food, soul food has a rich and deep history dating back to the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Where Does Soul Food Come From?

The soul food that we recognize today originated in the Deep South, consisting of Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama. This cuisine—now associated with social gatherings and comfort—was born from the need to survive. During the Transatlantic Slave Trade, Africans were given minimal food rations that were poor quality, meaning they did not have all the ingredients for the dishes they grew up eating in Africa. However, they were able to adapt to what they had and create variations of these traditional recipes with the rations they were given. Over time, these recipes evolved into the soul food we recognize today.

Culinary Pioneers

Countless people have contributed to developing and evolving soul food and the culinary industry to where it is today. Let’s investigate a few Black culinary pioneers who have left a lasting impact on society.

Lucille B. Smith

From Fort Worth, Texas, Lucille B. Smith was heavily involved with her community. She worked as a seamstress and private cook until 1927, when the Fort Worth Public School District hired her to be a teacher coordinator in the vocational educational program for Black students. In addition to this undertaking, she continued to cater dinners. In 1937, she was recruited to build the domestic training program at Prairie View A&M College for professors and instructors. While creating that program, she additionally formed the first collegiate Commercial Foods and Technology Department that had an apprentice training program, while simultaneously creating five service training manuals. Lucille was extensively dedicated to the development of her community and providing the youth of Fort Worth with quality culinary resources.

The 1940s sparked a blowout decade for Lucille. Originating as a church fundraiser, she created Lucille’s All-Purpose Hot Roll Mix: the first hot roll mix created. Her invention was an instant success: she raised $800 in profits (today that’s $17,528.34) , and orders continued to roll in. This caught the attention of grocery stores, leading her mix to become the first hot roll mix marketed in U.S. grocery stores. By 1948, she was selling over 200 cases a week.

Her story doesn’t end there. In 1974 Lucille founded Lucille B. Smith’s Fine Foods Inc., her family owned business which she became president. Her biscuits were served everywhere from American Airlines to the tables of first lady Eleanor Roosevelt and President Lyndon B. Johnson. Lucille’s contributions to the culinary industry can still be seen today (with evolutions to her mix such as Pillsbury’s own hot roll mix) and have cemented her place in culinary history.

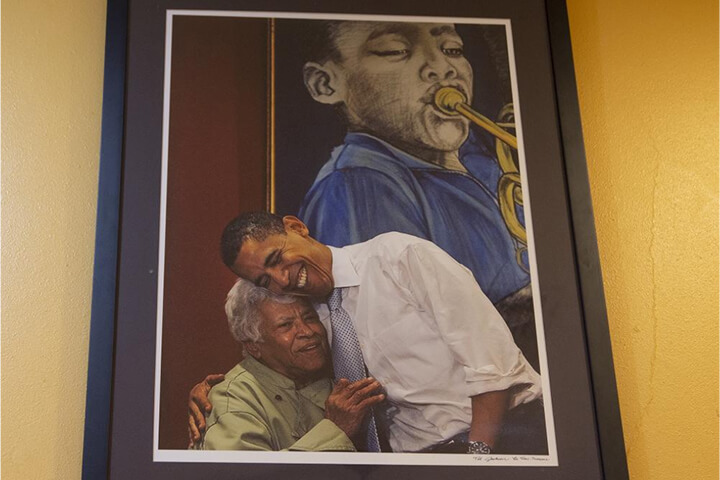

Leah Chase

Nicknamed the “Queen of Creole Cuisine,” New Orleans legend Leah Chase started her culinary journey waitressing in the French Quarter, where she was exposed to upscale restaurants frequented by White people. This inspired Chase to create an upscale dining experience for Black people. “I said well why can’t we have that for our people? Why can’t we have a nice space? So I started trying to do different things,” Chase said in an interview.

Those “different things” involved re-purposing the restaurant bearing her father-in-law’s (and husband’s) name from a sandwich shop where black patrons could get lottery tickets into an upscale restaurant where everyone of all races could dine. Sandwiches turned into Creole dishes, and the Dooky Chase Restaurant was born.

During the Civil Rights Movement, Dooky Chase became a gathering place for activists of all races. Black and White activists would meet at the restaurant to strategize about voter registration drives and numerous legal cases. Chase and her husband were violating the law by allowing Black and White patrons to eat together, but the restaurant was never raided. This is a miraculous feat considering that segregationists were “heavily invested in preventing interracial dining from becoming a widespread reality because it spoke to something even deeper: When people sit down together for a meal, they can’t help but recognize the humanity of those eating with them.” Chase and her husband demonstrated courage during a time when any protest of Jim Crow could result in fervent violence.

Dooky Chase was also frequented by many civil rights leaders. Ernest Morial, the city’s first Black mayor, Thurgood Marshall, and NAACP lawyer A.P. Tureaud would often work together during the day and head to Dooky’s for a meal.

Chase passed in 2019, but her legacy lives on at Dooky Chase. This “believer in the Spirit of New Orleans” created a fine dining experience where everyone can be brought together by food.

Honoring History

Juneteenth is one of the many major events in Black history that have shaped society. Celebrations honor this history, and the foods at these celebrations have deep historical roots as well: from red foods to soul foods. Soul food holds the stories of generations, and culinary pioneers like Lucille B. Smith and Leah Chase are two of the countless Black individuals who have shaped culinary history.